Jordan Treasure of Archaeological Sites

Jordan is a land rich in history. Since the dawn of civilization, Jordan has played an important role in trade between east and west because of its geographic location at the crossroads of Asia, Africa and Europe. It has been home to some of mankind’s earliest settlements and relics of many of the world’s great civilizations can still be found today. Jordan played a vital role in Roman, Biblical, the early Islamic and Crusader periods. From the moment you arrive, you get a sense of the past. All around are remnants of civilizations long since relegated to the history books, yet they still remain, stamped into the very fabric of this amazing Kingdom and etched into the soul of the people who live here. From the ancient Nabataean city of Petra, the miracle of the Dead Sea and Jordan Valley, the wonders of the Red Sea and Wadi Rum to the fine hotels, shopping centers and art galleries of modern Amman, Jordan truly is a nation rich in history and culture.

All around are remnants of civilizations long since relegated to the history books

AMMAN

Amman’s history spans nine millennia dating back to the Stone Age. It boasts one of the largest Neolithic settlements (c.6500 BC) ever discovered in the Middle East. Amman’s Citadel (al-Qala’a) became the focus of settlement from as early as the Early Bronze Age (3 200 – 2 000 BC). However, structural remains from this cultural phase are scanty and attested only in a few rock-cut tombs. In the Middle Bronze Age (2 000 – 1 550 BC), the Citadel was fortified with masonry sloping walls (Glacis). At that time, goods such as alabaster vases, faience vessels, and scarabs were imported from Egypt. In the Late Bronze Age (1 550 – 1 200 BC) commercial links expanded to include Cyprus and the Mycenaean islands. The Iron Age (1 200 – 539 BC), which coincides with biblical history, is when iron began to be used. In this period Jordan was split up into small states: Gilead in the north, Ammon and Moab in the centre, and Edom in the south. At the beginning of the 10th century BC King David conquered Rabbath Ammon as part of his expansionist policy. Uriah the Hittite, one of David’s officers, was killed in the front line of battle and David coveted his beautiful wife Bathshueba who became Solomon’s mother

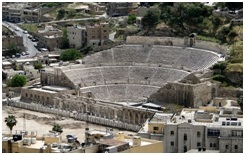

The Romans rebuilt the city with colonnaded streets, baths, a theatre and impressive public buildings.

Towards the 10th century BC Ammon regained its independence and Rabbath Ammon became the capital of the Ammonite State. A line of border fortresses forming a well integrated defensive system protected the western approaches to Rabbath Ammon. These fortresses or towers were built in the megalithic style and were square, rectangular, or circular. From the 8th century BC the area was ruled in succession by the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians. By the 3rd century BC the city had been renamed “Philadelphia” after its Ptolemaic ruler Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Seleucid and Nabataean rule followed until 63 BC, when it was absorbed into the Roman Empire and the Roman general, Pompey, annexed Syria and made Philadelphia part of the Decapolis League – an alliance of ten free city-states with overall allegiance to Rome. The Romans rebuilt the city with colonnaded streets, baths, a theatre and impressive Public buildings. Philadelphia flourished as one of the centers of the new Roman province of Arabia and of lucrative trade routes running between the Mediterranean and an interior which stretched to India and China as well as routes north and south. During the Byzantine period, when Christianity became the official religion of the Eastern Roman Empire the city was the seat of a Christian Bishop and two churches were constructed. By the early 7th century, Islam was spreading northwards from the Arabian Peninsula and, by 635AD, had embraced the land as part of its domain. The city returned to its original Semitic name of Ammon, or as it is known today, Amman.

JORDAN AND THE HUMAN JOURNEY

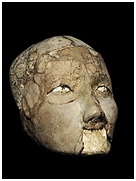

Some of the 32 clay figure statues from 'Ain Ghazal, Jordan, 6750 - 6570 BCE

Ain Ghazal - an archeological site located on the outskirts of Amman in Jordan - is one of the largest early villages known in the Near East. It dates as far back as 7250 BC, to the Neolithic period during which mankind made one of its most significant advances, the adoption of domestic plants and animals as primary subsistence sources. Excavations at Ain Ghazal have augmented considerably current knowledge of several aspects of the Neolithic. Of particular interest has been the documentation of a continuous or near continuous occupation from early through late Neolithic components and a concomitant dramatic economic shift. This shift was from a broad subsistence base relying on a variety of both wild and domestic plants and animals to an economic strategy reflecting an apparent emphasis on pastoralism.

'Ain Ghazal ranks as one of the largest known prehistoric settlements in the Near East.

Ain Ghazal witnessed what can be termed an explosion of symbolism

In its prime era circa 7000 BCE, it extended over 10-15 hectares (25–37 ac) and was inhabited by ca. 3000 people (four to five times contemporary Jericho). After 6500 BC, however, the population dropped sharply to about one sixth within only a few generations, probably due to environmental degradation (Köhler-Rollefson 1992). 'Ain Ghazal started as a typical aceramic Neolithic village of modest size. It was set on terraced ground at a valley-side, and was built with rectangular mud-brick houses that accommodated a square main room and a smaller anteroom. Walls were plastered with mud on the outside, and with lime plaster inside that was renewed every few years, Being an early farming community, the 'Ain Ghazal people cultivated cereals (barley and ancient species of wheat), legumens (peas, beans and lentils) and chickpeas in fields above the village, and herded domesticated goats. However, they also still hunted wild animals - deer, gazelle, equids, pigs and smaller mammals such as fox or hare. '

Ain Ghazal people buried some of their dead beneath the floors of their houses, others outside in the surrounding terrain. Of those buried inside, often later the head was retrieved and the skull buried in a separate shallow pit beneath the house floor. Also, many human remains have been found in what appears to be garbage pits, where domestic waste was disposed, indicating that not every deceased was ceremoniously put to rest. Why only a small, selected portion was properly buried and the majority just disposed of, remains unresolved. 'Ain Ghazal is renowned for a set of anthropomorphic statues found buried in pits in the vicinity of some special buildings that may have had ritual functions. These statues are half-size human figures modeled in white plaster around a core of bundled twigs. The figures have painted clothes, hair, and in some cases, ornamental tattoos or body paint. The eyes are created using cowrie shells with a bitumen pupil. In all, 32 of those plaster figures were found in two caches, 15 of them full figures, 15 busts, and 2 fragmentary heads. Three of the busts were two-headed, the significance of the two headed statues is not clear.

Amman was “a very ancient town and was ruined before the days of Islam

With various shifts in political power over the following centuries, Amman’s fortunes declined. During the Crusades and under the Mamluks of Egypt, Amman’s importance was overtaken by the rise of Karak in the south. By 1321 AD, it was reported that Amman was “a very ancient town and was ruined before the days of Islam, there are great ruins here and the river al-Zarqa flows through them.”

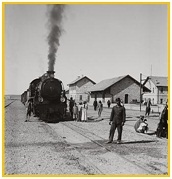

Under the Ottoman Empire, Amman remained a small backwater with As-Salt being the main town of the area. The weakening of Ottoman authority in the region coincided with the exodus of large numbers of Circassian and other persecuted Muslims from the Caucasus. They found refuge in the area and established settlement in Amman and other towns, e.g. Jerash, Suweileh, Wadi Seer, and Naur. Although they were mostly farmers, amongst these early settlers there were also gold and silversmiths and other craftsmen. It wasn’t long before they built rough roads linking these settlements. Commerce, once again, began to flourish. But it was the construction of the Hejaz Railway which really brought the city back to life. Linking Damascus with Medina, the railway passed through Amman. In 1902, once again, Amman became the centre of a busy trade route and its population began to grow. By 1905 the city held a mixed population of some 3000 people.

On 15th May 1923, the Emirate of Transjordan came into existence, with Emir Abdullah, a Hashemite and direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammed, Peace Be upon Him (PBUH), as its undisputed leader. On 22nd March 1946, Transjordan secured its independence. Two months later, Abdullah’s title of Emir, was changed to King, and the country was renamed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan with Amman as its capital. Over the ensuing decades the city has expanded and flourished to become a modern, lively, commercial metropolis of well over two million people. Excellent hotels and accommodation, gourmet restaurants, coffee shops, shopping centers, offices, and luxury villas have replaced older dwellings. However, there is still much of the old city to be admired.

Historical Sites

Amman offers a variety of historical sites from the Neolithic, Hellenistic, as well as late Roman to Arab Islamic periods. The Citadel - is a good place to begin a tour of the archaeological sites of the city. It is the site of ancient Rabbath-Ammon and excavations have revealed numerous Roman, Byzantine and early Islamic remains. Located on a hill, it not only gives visitors a perspective of the city’s incredible history but also provides stunning views of downtown Amman. Places of interest at the Citadel include: The Umayyad Palace complex, dating from about 730 AD; the Temple of Hercules, built during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180 AD); and the Byzantine Church, believed to date from the 6th or 7th century AD. Nearby attractions include: the restored Roman Theatre, which dates back to the 2nd century AD; the Roman Forum; the Nymphaeum; and Grand Husseini Mosque, built by Emir Abdullah in 1924 on the site of a much older mosque from the Umayyad period.

The most significant Roman structure, the Temple of Hercules, was built, according to an inscription, when Geminius Marcianus was governor of the Province of Arabia (AD 162-166), and was dedicated to the co-emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. It was not the first sanctuary on this site - remains have been found of an Iron Age shrine, probably dedicated to the Ammonite god Milcom; and the great exposed rock at the heart of the temple of Hercules is thought to have been part of an even earlier sanctuary. Stones and columns from the temple were re-used in the 5th/6th-century church that lies north-east of it, built to serve the spiritual needs of the small Christian community that remained on the citadel as part of

a residential and industrial complex. In the Umayyad period Roman building material was again re-used to create a palace and administrative offices in what may have been a second Roman temple precinct. It was the headquarters of the provincial governor, appointed by the Umayyad Caliphs in Damascus.

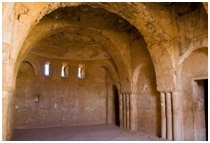

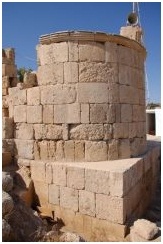

Still standing to its full height (though recently restored with a wooden dome), is the monumental entrance hall, a grand waiting room for those wishing to see the governor. Between this and the only modern building on the citadel (the Archaeological Museum) lie the remains of the Umayyad mosque, while to the west of the hall is the large circular cistern which supplied the palace with water.

The Jordan Archaeological Museum is a museum in the Citadel Hill in Amman, Jordan, built in 1951. It presents artifacts from archaeological sites in Jordan, dating from prehistoric times to the 15th century. The collections are arranged in chronological order and include items of everyday life such as flint, glass, metal and pottery objects, as well as more artistic items such as jewellery and statues. The museum also includes a coin collection. The museum houses the Ain Ghazal statues, which are the oldest statues ever made by a human civilization, and considered ones of the most important artifacts in human history. The museum also houses some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, as well as the only copper Dead Sea scroll.

The collections of the museum belong to the following periods:

The Paleolithic (1000, 000 – 10,000 years ago).

The Pre-pottery Neolithic (8300-5500 BC).

The Pottery Neolithic (5500-4300 BC).

The Chalcolithic (4300-3300 BC).

The Early Bronze Age (3300-1900 BC).

The Middle Bronze Age (1900-1550 BC).

The Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BC).

The Iron Age (1200-550 BC).

The Persian Period/Iron III (550-350 BC).

The Hellenistic Period (332-63 BC).

The Nabataean Period (312 BC-AD 106).

The Roman Period (63 BC – AD 324).

The Byzantine Period (AD 324 – 636).

The Islamic Era (AD 636 – the present).

a- The Umayyad Period (AD 661 – 750).

b- The Abbasid Period (AD 661 –750).

c- The Ayyubid/Mamluk Period (AD 1173 –1516)

Roman Theater was built during the reign of Antonius Pius (138-161 CE). The large and steeply raked structure could seat about 6,000 people: built into the hillside, it was oriented north to keep the sun off the spectators. It was divided into three horizontal sections (diazomata). Side entrances (paradoi) existed at ground level, one leading to the orchestra and the other to the stage. Rooms behind these entrances now house the Jordanian Museum of Popular Traditions on the one side, and the Amman Folklore Museum on the other side. The highest section of seats in a theatre was (and still is) called "The Gods". Although far from the stage, even there the sightlines are excellent, and the actors could be clearly heard, owing to the steepness of the cavea.

The Jordan Folklore Museum is located within the western section of the Roman Theatre in Amman. This museum was founded by the Department of Antiquities and officially opened in 1975. The museum houses items representing the following Jordanian cultures: The culture of the desert (Bedu), the culture of the villages (Reef), the culture of the towns and cities (Madineh). The collection of the museum represents items of daily life from the nineteenth and early twentieth century’s, such as: Costumes of the various areas in Jordan. (Utensils used for food preparation, making bread, coffee, and tea)

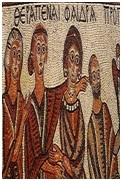

The Jordanian Museum of Popular Traditions was established in 1971. The museum is located within the eastern section of the Roman Theatre in Amman. Its aims are to collect Jordanian and Palestinian folk heritage from all over Jordan, to protect and conserve this heritage and to present it for future generations. The museum is also concerned with introducing our popular heritage to the world. The museum has five exhibition halls. The first hall is dedicated to the traditional costumes of the East Bank. In the second hall, the traditional jewelers and cosmetic items of the various regions in the East and West Banks are on display. The third hall contains a collection of Palestinian costumes and heard-dresses. In the fourth hall there is a collection of pottery and wooden cooking pots and food preparation vessels, as well as a collection of silver jewelers and bridal dresses from the West Bank. The fifth hall, which is in a vault of the Roman Theatre, houses a collection of mosaics from Byzantine churches in Jerash and Madaba.

MADABA

Just 33km southwest from Amman, Madaba has a very long history stretching from the Neolithic period. The town of Madaba was once a Moabite border city, mentioned in the Bible in Numbers 21:30 and Joshua 13:9. Madaba dates from the Middle Bronze Age. During its rule by the Roman and Byzantine Empires from the 2nd to the 7th centuries, the city formed part of the Provincia Arabia set up by the Roman Emperor Trajan to replace the Nabataean kingdom of Petra. During the rule of the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate, it was part of the southern Jund Filastin, The first witness of a Christian community in the city, with its own bishop, is found in the Acts of the Council of Chalcedon in 451, wherein Constantine, Metropolitan Archbishop of Bostra (the provincial capital) signed on behalf of Gaiano, "Bishop of the Medabeni." The resettlement of the city ruins by 90 Arab Christian families from Kerak, in the south, led by two Italian priests from the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem in 1880, saw the start of archaeological research. This in turn substantially supplemented the scant documentation available.

Archaeological research conducted between 1972 and 1991 showed that the Church of the Virgin was built above the hall of a Madaba mansion which had been decorated with lavish mosaics. The mansion was built in the first half of the VIth century over a Roman temple. Both the temple, which was round and had a high podium, and the Hippolytus Hall are on the south side of a paved courtyard. The western section of the Hippolytus mosaic was found 1.3 m below the mosaic floor of the church in 1905 by Sulayman Sunna', then the property owner. In 1982, the eastern section was unearthed.The mosaic, inspired by the Greek tragedy Hippolytus, decorates a hall of irregular dimensions: 7.3m wide on the eastern side and approximately 9.5 m long from east to west. The hall was originally covered by four north-south arches and was entered from the mansion's courtyard by a door on the north side of the northeast corner. Birds facing a flower decorate the intercolumnar spaces between the side pillars of the arches. A wide border of acanthus scrolls frames the central field of the mosaic which is sub-divided into three rectangular panels. The figures of the central panel of the carpet were partially destroyed when the hall was divided into two rooms in antiquity; Acanthus scrolls framing the central field incorporate hunting and pastoral scenes against a dark background. The four scrolls in the corners are decorated with personifications of the Seasons: Spring and autumn are on the west side, while summer and winter are to the east. All four are represented as Tyche in half bust, and each wears a turreted crown, In the grid of the west panel of the carpet, a section which was discovered in 1905, there are nilotic motifs: flowers and plants which alternate with aquatic birds. Two sea gulls with extended wings glide over the water

As noted, the central panel was partially damaged by a secondary wall, but it shows some of the major characters of the story of Phaedra and Hippolytus, a tragedy known to us from Euripides in Greek and Seneca in Latin. Captions reveal the names of the characters in the scene which shows handmaidens assisting Phaedra. Meanwhile a wet nurse turns toward Hippolytus who is accompanied by his ministers and a servant holding his mount. In the third panel, Aphrodite sits on a throne next to Adonis who holds a lance. A Grace presents to her a Cupid whom she threatens with a sandal. A second Cupid supports Aphrodite's bare foot, while a third watches, and a fourth has his head in a basket from which flowers fall; the basket and flowers allude to a poem in which a honeycomb with bees flying away is used to symbolize both the sweetness and sting of love. A second Grace grasps the foot of yet another Cupid who attempts to take refuge among the branches of a tree, and a third Grace chases a sixth Cupid. In order to show that this scene takes place in the open countryside, the artist added a bare-footed peasant girl carrying a basket with fruit on her shoulder and a partridge in her right hand.

Again, all the characters are identified by captions. An irregular area of the pavement near the entrance is decorated with a medallion in which a pair of sandals is framed by four birds. Along the eastern wall, there are personifications of three cities together with two sea monsters who challenge each other, as well as flowers and birds. The cities are Rome, Gregoria and Madaba. They are each depicted as Tyche seated on a throne and each holds a small cross on a long stuff in her right hand. Gregoria and Madaba wear turreted crowns on their heads, while Rome wears a helmet of a style which is typical in the official iconography of the era

The Church of the Map is the Modern Greek Orthodox Church of St. George, built in 1884 over a ruined Byzantine church from the time of Justinian (527 - 565). Its mosaic map, belonging to the original Byzantine foundation, is the oldest existing map of Palestine. It is now greatly deteriorated, with many sections missing. This map of Jerusalem is one area of the mosaic that fortunately survives. East is to the top of the photo, reflecting the traditional orientation of Byzantine churches. The Holy City is captioned in red letters, "Hagia Polis Ierousa". The Damascus Gate is on the left (north), and the upside-down Church of the Holy Sepulchre extends downward from the middle of the colonnaded main street. Writing around the city indicates the lands of the Tribes of Israel ("Benjamin," for example, written left above the Damascus Gate) and other places of Biblical significance.

Madaba Archaeological Museum

This museum was founded in 1974, this museum holds artifacts and finds, that have been recovered during excavations in many archaeological sites in Madaba region. These artifacts consist mainly of pottery and glass vessels, metalwork, coins and mosaic floors. Their dates range from the Iron Age to the Islamic periods

Madaba Archaeological Park

Encompasses the remains of several Byzantine churches, including the fantastic mosaics of the Church of the Virgin

And the Hippolytus Hall, Several buildings adjacent to the complex are housing a school for the restoration and conservation of ancient mosaics.

There is an impressive collection of restored Herodian and Byzantine mosaics on display in the Madaba Archaeological Park & the Madaba Museum

MOUNT NEBO

10 minutes away from Madaba, Mount Nebo is the place where Moses viewed the holy land of Canaan and is believed to have been buried. It is the most revered holy site in Jordan and a place of pilgrimage for early Christians. Mount Nebo’s first church was built in the late fourth century to mark the site, Six tombs, from different periods, have been found hollowed out of the rock beneath the mosaic-covered floor of the Moses Memorial Church at Mount Nebo. In the present presbytery you can see remnants of mosaics, the earliest of which is a panel with a braided cross.

The Serpentine Cross, which stands just outside the sanctuary, is symbolic of the brass serpent taken by Moses into the desert and the cross upon which Jesus was crucified, The Franciscan Archaeological Institute in Jordan aims at preserving the archaeological heritage of Mount Nebo, the nearby city of Madaba and the surrounding area. On the highest point of the mountain, Syagha, the remains of a church and monastery were discovered in 1933. The church was first constructed in the second half of the 4th century to commemorate the place of Moses' death. The church design follows a typical basilica pattern. It was enlarged in the late fifth century A.D. and rebuilt in A.D. 597. The church is first mentioned in an account of a pilgrimage made by a lady Aetheria in A.D. 394.

UMM AR-RASAS (Ancient Mayfa’a)

Approximately 85 km away from Amman, Mayphaath is listed as one of the places on the Moab plateau (1 Chr. 6:79; Jer. 48:21). Is an archeological site in Jordan which contains ruins from the Roman, Byzantine, and early Muslim civilizations. The majority of the site has not been excavated. Among the portions excavated so far include a military camp and several churches. For its unique blend of civilizations, Um er-Rasas was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004. The most important discovery on the site was the mosaic floor of the Church of St Stephen. It was made in 785 (discovered after 1986). The perfectly preserved mosaic floor is the largest one in Jordan. On the central panel, hunting and fishing scenes are depicted, while another panel illustrates the most important cities of the region including Philadelphia (Amman), Madaba, Esbounta (Heshbon),Belemounta (Ma'an), Areopolis (Ar-Rabba), Charac Moaba (Karak), Jerusalem, Nablus, Caesarea, and Gaza.

The frame of the mosaic is especially decorative. Six mosaic masters signed the work: Staurachios from Esbus, Euremios, Elias, Constantinus, Germanus, and Abdela. It overlays another, damaged, mosaic floor of the earlier (587) Church of Bishop Sergius. Another four churches were excavated nearby with traces of mosaic decoration. Less than 2km north of the fortified town, the highest standing ancient tower of Jordan puzzles King Herod¡¦s hilltop stronghold at Mukawir. „´ the specialists: the 15-metre high, Square tower with no door or inner staircase, thought to be a stylite tower, is now inhabited by birds.

Dhiban the capital of Mesha, king of Moab

Dhiban is a town located in Madaba Governorate, approximately 70 kilometers south of Amman and east of the Dead Sea. Previously nomadic, the modern community settled the town in the 1950s. Today, The ancient settlement lies adjacent to the modern town. Excavations have revealed that the site was occupied intermittently over the past 5,000 years, its earliest occupation occurring in the Early Bronze Age in the third millennium BCE. The site's extensive settlement history is in part due to its location on the King's Highway, a major commercial route in antiquity. The majority of evidence for this population is concentrated in a 15 hectare tall. The release of the Mesha Inscription in 1868 led to an upsurge in visitors to the town (including tourists and scholars) due to its ostensible confirmation of biblical passages.

The first substantial settlement at Dhiban does tell was during the Early Bronze Age. Archaeological evidence for a habitation of the tell between the Early Bronze Age and Iron Age has not yet been found. However, the disturbed archaeological context at the site means that this might not be definitive. Dhiban might correspond with the town “Tpn” or “Tbn” found in Egyptian texts from the reigns of Thutmoses III, Amenhotep III, and Rameses II. Though it had an Early Bronze Age settlement, the period about which most is known is the Iron Age, especially the 9th century BC, when it was the capital of Mesha, king of Moab.

Tell Hesban the highest summits of Moab Mountains

The site of Tell Hesban, 9 km. north of Madaba, Jordan, was excavated by Andrews University, in cooperation with the American Schools of Oriental Research and the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (Five seasons, 1968 to 1976). Evidence from the site suggests that it was first occupied in Iron Age I (ca. 1200 B.c.) and continuously thereafter, except for two gaps in occupation (6th century to ca. 198 B.c., and A.D. 969 to 1200). This present research has limited itself to Tell Hesbin Strata 15 through 11 (ca.198 B.C. to A.D. 363). Research has been based primarily on the records and remains of the five seasons of excavation, but has included a search for cultural parallels from other Palestinian and Syrian sites, as well as an attempt to place Tell Hesbh (Roman Esbus) in its historical setting in the periods represented by each stratum.

The oldest excavated site in Jordan Located north of Madaba, at 21 km southwest of Amman, the highest summits of Moab Mountains, Tools found at Hisban indicate the old rich history of the place since the Paleolithic Period, early Bronze and Iron Ages. It was a well-fortified city, and was the capital of the Amorites until 1400 B.C. it was called Esbus during the Hellenistic Period (332-164 B.C.) and has a citadel walls with four cornered towers and became a temple and administrative site with many caves and underground tunnels to serve many purposes at the time, Hisban reached its maximum population during the 4th century A.D. and became part of the Esbus-Jerusalem and Bilanova roads, remains and evidence indicates that Hisban was at its most prosperous during the Byzantine Period (330-640 A.D.), remains of a church and water cisterns were used to supply large population. Hisban was conquered peacefully by Muslims during the 630s and through the 640s; Christians remained in the site for some time during the Umayyad period (636-713 A.D.).

MUKAWIR (Machaerus)

Located 24 km southeast of the mouth of the Jordan River on the eastern side of the Dead Sea, is Machaerus (Mukawir in Arabic). The 1st Century AD Roman-Jewish historian, the palace/fort of Herod, overlooking the Dead Sea region and the distance hills of Palestine and Israel,

The fortress of Machaerous was one of the strongholds of the defence system of the Jewish state in the eastern province of Perea on the south boundary with the Nabataeans of Petra, The naturally defended site was chosen by Alexander Janneus to build the fortress (BJ VII, 6, 2). It was demolished by Gabinius (57 B.C.E.). Aristobulus and his son Alexander sought refuge among the ruins (BJ I, 8, 6). King Herod rebuilt the fortress (BJ VII, 6, 2-3). Upon the death of Herod, his son Herod Antipas inherited it. In the fortress John the Baptist was thrown into prison and put to death (AJ XVIII, 5, 1-2). On the death of King Agrippa I (44 C.E.), the fortress came under the direct administration of the Roman Praefectus Judaeae. At the outbreak of the Jewish Revolt (66 C. E.) the Roman garrison abandoned the fortress into the rebel's hands, who held it up to 72 C. E. (BJ II, 18, 6).

In that year Lucilius Bassus besieged the fortress, took it and destroyed it (BJ VII, 6,). Later Byzantine sources mention only the village of Machaberos (Georgii Cyprii Descriptio, n. 1082; Cyrilli Vita Sabae, 82). With Masada, Hyrcania, Alexandreion and Cypros, Machaerous is one of the fortresses that Herod the King has inherited from the Hasmoneans. It was not inhabited before the Hasmoneans, nor was it ever reoccupied after the destruction of the Romans. On top of the mountain, surrounding the crest, he built a fortress wall, 100 meters long and 60 meters wide with three corner towers, each sixty cubits (90 ft) high.

The palace was built in the center of the fortified area. Numerous cisterns were provided to collect rain water. Within the fortified area are the ruins of the Herodian palace, including rooms, a large courtyard, and an elaborate bath, with fragments of the floor mosaic still remaining. Farther down the eastern slope of the hill are other walls and towers, perhaps representing the "lower town," of which Josephus also speaks. Traceable also, coming from the east, is the aqueduct that brought water to the cisterns of the fortress. Pottery found in the area extends from late Hellenistic to Roman periods and confirms the two main periods of occupation, namely, Hasmonean (90 BC-57 BC) and Herodian (30 BC-AD 72), with a brief reoccupation soon after AD 72 and then nothing further—so complete and systematic was the destruction visited upon the site by the Romans.

THE JORDAN VALLEY & THE DEAD SEA(Lowest point on the face of the earth)

The Dead Sea is less than an hour’s drive from Amman; The Jordan Valley is part of the Great Rift Valley that runs from Turkey to east Africa, formed by a series of geological upheavals millions of years ago. The Dead Sea originally stretched the entire 360 kilometers, from Aqaba in the south, to Lake Tiberius in the north. The therapeutic water of the Dead Sea, combined with the valley’s fertile land and warm climate, have attracted people to live, hunt and farm in the area since the Stone Age. Over 200 archaeological sites have been discovered, but there are believed to be many more. For Christians, this region inspires their faith.

This is the place where God first spoke to man. It is the Holy Land where God gave his Ten Commandments to Moses, where Job suffered and was rewarded for his faith, Where Jesus was baptized by John, and where Jacob wrestled with the angel of God. In the Book of Genesis, God refers to the Jordan River Valley around the Dead Sea, as the “Garden of the Lord”, and it is believed to be the location of the Garden of Eden. The infamous cities of Sodom and Gomorrah and many other places were the subjects of dramatic and enduring Old Testament stories, including that of Lot, whose wife turned into a pillar of salt for disobeying God’s will. Many of these sites and others in the region are also significant Holy places for Muslims, who can find a plethora of religious destinations that are important to the development of Islam

The Jordan Valley is home to many tombs of the Prophet Mohammad’s (PBUH) venerable companions and military leaders who fell in battle or succumbed to the Great Plague in the 18th year after the Hijra. Jordan Valley is one of the world’s most amazing places, a dramatic, And beautiful landscape, which at the Dead Sea, is over 410 meters (1,312 ft.) below sea level making it the lowest point on the face of the earth.

The Jordan Valley region is believed to have been home to five Biblical cities: Sodom, Gomorrah, Adman, Zebouin, and Zoar. The area opposite Jericho has been identified for nearly two millennia as the place where Jesus Christ was baptized by John the Baptist. A region of some 8 square kilometers on the east bank of the Jordan River, archaeologists have identified and examined over 30 different archaeological remains. Numerous artifacts confirm the area was inhabited in the Early Roman period, the time of Jesus and John the Baptist.

Located some 11 kilometers north of the Dead Sea shore, about a 40-minute drive from Amman, Bethany beyond the Jordan is fast becoming a major new destination for Christian pilgrims. The key discoveries are the Byzantine monastery and earlier Roman-era remains at Tell al-Kharrar; several smaller Byzantine churches, chapels, monks' hermitages, caves, and hermit cells; a large Byzantine multi-church complex; a ceramic pipeline bringing water to the site from several kilometers east; a large plastered pool and adjacent khan halfway between Tell al-Kharrar and the Jordan; another pilgrims' rest station and khan several kilometers east, on the ancient pilgrimage route to Mount Nebo. The discoveries have excited archaeologists and biblical geographers alike.

Somewhere would be the cities mentioned in the Book of Genesis which were said to have been destroyed in the time of Abraham, Sodom and Gomorra (Genesis 18)

And the three other

"Cities of the Plain" - Admah, Zeboim and Zoar (Deuteronomy 29:23)

This seems the only site where textual, archaeological and traditional evidence converge. The puzzle about the precise site of Jesus' baptism is complicated by several factors: the different ancient names used to designate the area, the imprecise narrative in the biblical text, and the different modern sites where pilgrims commemorate the baptism, the main mound at Tell al-Kharrar has long been called Elijah's Hill, Tell Mar Elias in Arabic. This reflects its identification as the place from where the Prophet Elijah ascended to heaven (2 Kings 2:5-14). Today the area is called Al-Maghtas, "the place of baptism" or "of immersion." Byzantine-era Christian testimony remains one of the strongest sources of evidence for placing Jesus' baptism here.

Starting in the 3rd century, Christian writers and pilgrims associated this region with Elijah's ascension and Jesus' baptism. The anonymous Pilgrim of Bordeaux in 333 located the site of Jesus' baptism at five Roman miles (7,400 meters) north of the Dead Sea shore - near where Wadi al-Kharrar joins the Jordan River. According to the pilgrim Theodosius' account (dated around 530), in the late-5th century the Emperor Anastasius built the first church to commemorate Jesus' baptism on the east bank of the Jordan. The Pilgrim of Piacenza (570) first specified that the baptism site was directly opposite the monastery of St. John, whose rebuilt remains still stand on a hilltop some 800 meters west of the river, in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. The Pilgrim of Piacenza was the first to mention the spring of John the Baptist at the site of Tell al-Kharrar, 3 kilometers east of the river. Writing between the 9th and 11th centuries, the monk Epiphanius mentioned a cave near a spring nearly 4.5 kilometers east of the river, where John the Baptist lived and baptized. The early 12th-century traveler Abbot Daniel mentioned a grotto of St. John the Baptist east of the river. The rich textual evidence from the 4th through 12th centuries reveals a consistent tradition locating John the Baptist's settlement near the spring source of Wadi al-Kharrar, in an area characterized by springs and caves some two kilometers east of the Jordan River.

The excavated main complex at Tell al-Kharrar comprises structures on and around the small hill adjacent the spring at the head of Wadi al-Kharrar. Artifact evidence shows that the site was inhabited from the Late Hellenistic/Herodian and Early Roman periods (2nd century BC to 2nd century AD), through the Late Byzantine and early Islamic periods (5th to 8th centuries AD), and again in late Ottoman centuries. The strongest evidence for a Chrstian-era settlement here comes from the excavated remains of heavy stone jars, a distinctive feature of local Jewish communities. Father Michele Piccirillo of the Franciscan Archaeological Institute in Jerusalem and Mount Nebo, one of those who rediscovered the site in August 1995, identified these fragments. He believes that, along with remains of large ceramic storage jars, they are clear proof of a settled population, which he identifies as Bethany beyond the Jordan. One of the three churches, discovered in 1999 on the west side of the hill, was built around a natural cave used in John the Baptist's days. This may be the cave Byzantine pilgrims called "the cave of John the Baptist." A man-made water channel started at the front of the cave, and traveled for about 6 meters until it spilled its water into the south bank of the Wadi al-Kharrar. Over 30 Byzantine-era sites identified from the Jordan River eastwards to Wadi al-Kharrar and Wadi al-Gharabah. They formed stations along the pilgrims' route from Jerusalem to the Jordan River and Mount Nebo.

Perhaps the key discovery related to the commemoration of the baptism tradition on the east bank of the river is the large multi-church Byzantine-era complex, about 100 meters east of the Jordan. It comprises the remains of four distinct churches from the 5th-6th century. Three are superimposed on each other, comprising the original church and two re-builds. The fourth is a smaller structure built about 30 meters east. The original church here was almost certainly the Church of St. John the Baptist, described by Byzantine texts as built by Emperor Anastasius. Byzantine-era accounts said the church was built on arched arcades on stone piers. These have been exposed by recent excavations, further south; just outside a place called Safi (Biblical Zoar) is the cave where Lot and his daughters took refuge after the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. A small church commemorates the spot.

Karak (Qir of Moab)

Karak (also Kerak) is known for the famous crusader castle Kerak. The castle is one of the three largest castles in the region, the other two being in Syria. Karak is the capital city of Karak Governorate. Karak, once a Kingdom, lies 140 km to the south of Amman on the King's Highway. An ancient Crusader stronghold, it is situated on a hilltop about 1000 meters above sea level and is surrounded on three sides by a valley. Karak has a view of the Dead Sea. A city of about 20,000 people has been built up around the castle, and it has buildings from 19th century Ottoman period. The town is built on a triangular plateau, with the castle at its narrow southern tip, but it is undoubtedly Karak Castle which dominates. Al Karak has been inhabited since at least the Iron Age, and was an important city for the Moabites (who called it Qir of Moab). In the Bible it is called Qer Harreseth, and is identified as having been subject to the Assyrian empire; in the Books of Kings (16:9) and Book of Amos (1:5,9:7),it is mentioned as the place where the Syrians went before they settled in the regions north of Palestine, and to

which Tiglath-Pileser III sent the prisoners after the conquest of Damascus. In 1958 the remains of an inscription was found in wadi al Karak that has been dated to the late ninth century BC. The area eventually fell under the power of the Nabateans. The Romans (support from the Ghassanids or Ghassasinah) conquered it from them in 105 AD. The Al-Ghassasneh (Ghassanids) tribe is believed to be the first tribe to inhabit the site of modern al-Karak. The tribe consists of the families: Suheimat, Dmour, Mbaydeen, Adaileh, Soub, Karakiyeen. During the late Hellenistic Period, Al Karak became an important town taking its name from the Aramaic word for town, Kharkha.[4] Under Roman rule the city was known as Areopolis, and in Late Antiquity as Harreketh. Under the Byzantine Empire it was a bishopric seat, housing the much venerated Church of Nazareth, and remained predominantly Christian under Arab rule.

In 1132 King Fulk, the Crusader king of Jerusalem, made Pagan the Butler Lord of Montreal and Oultrejourdain, the lands east of the River Jordan and the Dead Sea. Pagan made his headquarters at al-Karak were he built a castle on a hill called by the crusaders Petra Deserti - The Stone of the Desert. His castle, much modified, dominates the town to this day. The castle was only in Crusader hands for 46 years. It had been threatened by Saladin's armies several times but finally, surrendered in 1188, after a siege that lasted more than a year. Saladin's younger brother, Al-Adil was governor of the district until becoming ruler of Egypt and Syria in 1199. The castle played an important role as a place of exile and a power base several times during the Mamluk Sultanate.

Its significance lay in its control over the caravan route between Damascus and Egypt and the pilgrimage route between Damascus and Mecca. In the thirteenth century the Mamluke ruler Baibars used it as a stepping stone on his climb to power. In 1389 Sultan Barquq was exiled to al-Karak were he gathered his supporters before returning to Cairo. Al-Karak was the birth place of Ibn al-Quff, an Arab physician and surgeon and author of the earliest medieval Arabic treatise intended solely for surgeons.

The castle extends over a southern spur of the plateau. It is a notable example of Crusader architecture, a mixture of European, Byzantine, and Arab designs. Its walls are strengthened with rectangular projecting towers and long stone vaulted galleries are lighted only by arrow slits. The castle has a deep moat that isolated it from the rest of the hill on the West. Such a moat is a typical feature of spur castles. The steep slopes of the spur are covered by a glacis. While Kerak is a large and strong castle, its design is less sophisticated than that of concentric crusader castles like Krak des Chevaliers, and its masonry is comparatively crude.

The Karak Archaeological Museum

Established inside the old castle, has remains from the Moabite period in the first millennium BC, going through the Nabataean, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic and Crusader periods. The museum was opened in 1980. The main part of the museum is a large hall in a vault of the castle, used as living quarters for soldiers in the Mameluk period. The collections date from the Neolithic up to the late Islamic periods and come from the Karak and Tafila regions. Among the sites is Bab Adh-Dhra’, famous for its Bronze Age burials. The museum houses remains of skeletons and pottery from the Bab Adh-Dhra' graves; Iron Age II artefacts from Buseirah; Byzantine glass vessels and inscriptions, and Roman and Nabataean artefacts from Rabbah and Qasr.

Shawbak castle (Le Krak de Montreal) lonely reminder of former Crusader glory

Montreal is a Crusader castle on the eastern side of the Arabah, perched on the side of a rocky, conical mountain, looking out over fruit trees below. The ruins, called Shoubak or Shawbak in Arabic, are located in modern town of Shoubak in Jordan. The castle was built in 1115 by Baldwin I of Jerusalem during his expedition to the area where he captured Aqaba on the Red Sea in 1116.

Originally called 'Krak de Montreal' or 'Mons Regalis', it was named in honour of the king's own contribution to its construction (Mont Royal).

It was strategically located on a hill on the plain of Edom, along the pilgrimage and caravan routes from Syria to Arabia. This allowed Baldwin to control the commerce of the area, as pilgrims and merchants needed permission to travel past it. It was surrounded by relatively fertile land, and two cisterns were carved into the hill, with a long, steep staircase leading to springs within the hill itself.

It remained property of the royal family of the Kingdom of Jerusalem until 1142, when it became part of the Lordship of Oultrejordain. At the same time the centre of the Lordship was moved to Kerak, a stronger fortress to the north of Montreal. Along with Kerak, the castle owed sixty knights to the kingdom. It was held by Philip de Milly, and then passed to Raynald of Châtillon when he married Stephanie de Milly. Raynald used the castle to attack the rich caravans that had previously been allowed to pass unharmed. He also built ships there, and then transported them overland to the Red Sea, planning to attack Mecca itself. This was intolerable to the Ayyubid sultan Saladin, who invaded the kingdom in 1187. After capturing Jerusalem, later in the year he besieged Montreal. During the siege the defenders are said to have sold their wives and children for food, and to have gone blind from "lack of salt." Because of the hill Saladin was unable to use siege engines, but after almost two years the castle finally fell to his troops in May 1189, after which the defenders' families were returned to them. The Mameluks later captured and rebuilt it, little remains of the original Crusader fortifications. Although it has never been fully excavated, it is known that there was a set of three walls, which partially remain. The towers and walls are decorated with carved inscriptions dating from 14th century Mameluke renovations, but the inside is ruinous. Near the gatehouse, a well with over 350 dangerously slippery spirals, rock-cut steps descends to a spring.

PETRA "a rose-red city half as old as time"

Petra is a 3-hour drive south from Amman on the modern Desert Highway, or 4 hours on the more scenic Kings’ Highway. The ancient city of Petra is one of Jordan’s national treasures and by far its best known tourist attraction. Located about three hours south of Amman, Petra is the legacy of the Nabataeans, an industrious Arab people who settled in southern Jordan more than 2 000 years ago. Admired then for its refined culture, massive architecture and ingenious complex of dams and water channels, Petra is now a UNESCO world heritage site that enchants visitors from all corners of the globe.

Before Alexander’s conquest, a new civilization had emerged in southern Jordan

Evidence suggests that settlements had begun in and around Petra in the eighteenth dynasty of Egypt (1550-1292 BCE), (the cleft in the rock)

Although most of what can be seen at Petra today was built by the Nabataeans, the area is known to have been inhabited from as early as 7,000 to 6,500 BC. Evidence of an early settlement from this period can still be seen today at Little Petra, just north of the main Petra site. By the Iron Age (1,200 to 539 BC), Petra was inhabited by the Edomites.

They settled mainly on the hills around Petra rather than the actual site chosen by the Nabataeans. Although the Edomites were not proficient at stone masonry, they excelled at making pottery and it seems they passed this craft on to the Nabataeans. A recently excavated kiln discovered at Wadi Musa, indicates that Petra was a regional centre for pottery production up until the late 3rd century AD, after which it fell into decline. The Nabataeans were a nomadic Arab people from Arabia who began to arrive and slowly settle in Petra at the end of the 6th century BC. It seems their arrival at Petra was unplanned, as their original intent was to migrate to southern Palestine. No doubt they found this place attractive with its plentiful supply of water, defensive canyon walls and the friendly Edomites, with whom it seems they had a peaceful coexistence. By the 2nd century BC, Petra had become a huge city encompassing around ten square kilometers, and was the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom. Primarily, the Nabataeans were farmers. They cultivated vines and olive trees and bred camels, sheep, goats and horses. They were skilled at water management and built a complex network of channels and cisterns to bring water from a plentiful source at Ain Musa several kilometers away

Petra flourished under Roman rule and many Roman style amendments were made to the city, including the enlargement of The Theatre, paving of the Colonnaded Street, and a triumphal arch was built over the entrance to the Siq. When the Roman Emperor, Hadrian, visited the site in 131AD, he named it after himself, Hadriane Petra. The Romans took control of the lucrative trade routes and diverted them away from Petra. It was the beginning of the end for the Nabataeans, whose wealth and power gradually fell into decline. Evidence of the Nabataeans at Petra was dwindling and when Christianity spread across the Byzantine Empire, Petra became the seat of a bishopric and a monument was converted to a church, which is the Urn Tomb. Recent excavations have Exposed three churches, one of them paved with colored mosaics.

In 661 AD the Muslim Umayyad dynasty established its capital in Damascus, Syria and Petra found itself isolated from the seat of power. This, combined with a series of strong earthquakes, marked the end of this once mighty city. Although there is some evidence that the place was, once again, used as a stopping place for caravans in the 13th to 15th centuries, it was eventually abandoned and became a place inhabited and fiercely guarded, by the local Bedouins. This once magnificent city was forgotten entirely by the western world until the Swiss traveler, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, disguised as an Arab, rediscovered it on the 22nd August, 1812.

Petra’s most famous monument, the Treasury, appears dramatically at the end of the Siq. Used in the final sequence of the movie “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade”, the towering facade of the Treasury is only one of myriad architectural wonders to be explored at Petra. Various walks and climbs reveal literally hundreds of rock cut tombs and temple façades, funerary halls and rock reliefs. There’s also a 3000-seat theatre from the early 1st century AD, a Palace Tomb in the Roman style, and a gigantic 1st century Deir (Monastery).

On the authority of Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews iv. 7, 1~ 4, 7) Eusebius and Jerome (Onom. sacr. 286, 71. 145, 9; 228, 55. 287, 94) assert that Rekem was the native name and Rekem appears in the Dead Sea scrolls as a prominent Edom site most closely describing Petra and associated with Mount Seir. But in the Aramaic versions Rekem is the name of Kadesh, implying that Josephus may have confused the two places. Sometimes the Aramaic versions give the form Rekem-Geya which recalls the name of the village El-ji, southeast of Petra. The Semitic name of the city, if not Sela, remains unknown.

The passage in Diodorus Siculus (xix. 94–97) which describes the expeditions which

Antigonus sent against the Nabataeans in 312 BCE is understood to throw some light upon the history of Petra, but the "petra" referred to as a natural fortress and place of refuge cannot be a proper name and the description implies that the town was not yet in existence. The Rekem Inscription in 1976, the only place in Petra where the name "Rekem" occurs was in the rock wall of the Wadi Musa opposite the entrance to the Siq. About twenty years ago the Jordanians built a bridge over the wadi and this inscription was buried beneath tons of concrete. A modest shrine commemorating the death of Aaron, the brother of Moses, was built in the 13th century by the Mameluke Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammed, High atop Mount Aaron in the Sharah range.

Nabataeans, an Arabian nation in modern Jordan

Petra Archaeological Museum

The old archaeological museum at Petra is located in an ancient Nabataean cave on the slope of Al-Habis. The museum was opened in 1963 and it is composed of one main hall and two side rooms. The collection represent finds from excavations in the Petra region, dating from the Edomite, Nabataean, Roman and Byzantine periods, with special emphasis on architectural decorative elements and stone sculpture. The exhibits in this museum are presently in the process of rearrangement after the opening of the Petra Nabataean Museum.

Petra Nabataean Museum

This museum was opened in 1994, with three main exhibitions halls. The first hall introduces the history of Petra and the Nabataeans, the geology of the Petra region, as well as special examples representing Neolithic food processing, Edomite pottery, Nabataean sculpture, and hydraulic engineering. The second hall is dedicated to specific excavations, starting with the Neolithic village at Beida, then the Iron Age settlement at Tawilan, the Nabataean and Late Roman houses on Az-Zanter, the Zurrabah pottery kilns dated to the late 1st century BC through to the 6th century AD, the Nabataen Temple of the Winged Lions, the Qasr Al-Bint Temple in the city centre, and finally the Petra Church Project.

A special exhibit representing earthquakes, Nabataean trade and Petra in the medieval period can also be seen in this hall. The third hall deals with various artefacts, such as jewellery, lamps, bronze statuettes, terracotta figurines, pottery, and coins, with special emphasis on the manufacturing processes.

AQABA (Ayla)

Famed for its preserved coral reefs and unique sea life, this Red Sea port city was, in ancient times, the main port for shipments from the Red Sea to the Far East. Its museum houses a collection of artifacts collected in the region, including pottery and coins. From as far back as five and a half thousand years ago Aqaba has played an important role in the economy of the region. It was a prime junction for land and sea routes from Asia, Africa and Europe, a role it still plays today. Because of this vital function, there are many historic sites to be explored within the area, including what is believed to be the oldest purpose built church in the world.

Aqaba’s long history dates back to pre-biblical times, when it was known as Ayla. According to the Old Testament, King Solomon built a naval base at Ezion Geber, erroneously identified with the Edomite site of Tell Al-Khaliefeh, near the northern border of modern Aqaba. Documentary sources suggest that Ayla (variously spelled as Aila, Ailana, Leena, and Eilath) was founded as a Nabataean city. In 106 AD the Roman emperor Trajan annexed the Nabataean Kingdom and incorporated it in the newly created Province of Arabia. The same emperor built the Via NovaTrajana which extended from Aila to Bostra in Southern Syria. In the late 3rd century AD the Legion X Fretensis, which was based in Jerusalem, moved to Aila and garrisoned there.

In the Byzantine period when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman eastern Empire, the city became a station for pilgrims visiting Mt. Sinai. We are also informed that the architect in charge of building the monastery at Mt.Sinai in the mid 6th century was Stephanos from Ayla.

Muslim rule in Ayla began in 630AD when its bishop, “Yohanna bin Ru’bah” made a peace treaty with Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). One of the articles of the peace treaty guaranteed the inhabitants on Ayla “protection of their ships and caravans on sea and land”. This suggests the continued importance of commerce to the city’s economy up to the eve of the Muslim conquest. Two decades later the Arab Muslims founded a new walled town which flourished from the mid 7th to the early 12th centuries. Excavations in the centre of Aqaba, near the beach, uncovered a walled town measuring 165 x 140 meters. The enclosure was a series of U-shaped towers with a single gate pierced in the centre of the city. The intersection point was marked by a tetrapylon (a four-way arch) which in the second half of the 10th century became the residence of a wealthy merchant. The eastern quadrant was occupied by a hypostyle mosque. By the 1116 AD when Baldwin I, the king of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, arrived at Ayla , the inhabitants were too weak to offer any serious resistance, and in the course of the 12th century the walled town was abandoned, and a new settlement sprang up further south near the present Mameluke Fort It was the Mameluke Sultans of Egypt who took control of the region, renamed the city Aqaba and, in the early 16th century, built the town’s famous Mameluke Fort.

The Mamelukes were followed by the Ottomans, who ruled Aqaba for four centuries.

The Mameluke Fort, one of the main historical landmarks of Aqaba, was rebuilt by the Mamelukes in the sixteenth century. Square in shape and flanked by semicircular towers, the fort is marked with various inscriptions marking the latter period of the Islamic dynasty. Excavations at the ancient site of Ayla revealed a gate and city wall along with towers, buildings and a mosque. Other places of interest include a mud brick-building believed to be the earliest purpose-built church in the world

Aqaba’s long history dates back to pre-biblical times, when it was known as Ayla

Aqaba Archaeological Museum

Aqaba Archaeological Museum lies adjacent to the historic castle of Aqaba, in the city that holds the same name in Jordan. The museum houses artifacts from the 7th to the early 12th century AD. The building that hosts the museum was the palace of Sharif Hussein Bin Ali, the founder of the Hashemite dynasty, and was built shortly after World War I in 1917. The museum's collections include a large inscription of a Quranic verse that was hanging on top of the eastern gate of the city in the 9th century, as well as golden coins that date back to the Fatimides and other coins from the kingdom of Segelmasa in Morocco.

Saved dolmen field in Jordan - a new attraction

The Dolmen was a structure like a ‘table’ of stones created by a capstone – weighing up to 50 tons – on top of three or four standing stones. The structure would then be buried, creating an artificial cave.

Dolmens are from the Early Bronze Age (3600-3000 BC) and some experts say they could be even older, from the Chalcolithic era (that's 4500-3500 BC). There are around 300 dolmens on site, so it should become an interesting park to visit; there are so many things to look at from so many different times. There are many examples of flint dolmens in the historical villages of Johfiyeh and Natifah in northern Jordan. The greatest number of dolmens is around Madaba, like the ones at Al Faiha village, 10 km to the west of Madaba. Two dolmens are in Hisbone, and the most have been found at Zarqa Ma'in at Al-Murayghat, a Dolmen also field near Damiyah, a village located north of Salt, in the Jordan Valley, has been on the World Monuments Watch list.

Dolmens at Al Faiha, Wadi Jadid located within 10 km to the south west of Madaba city at Al Fiha village. This Wadi is a field of dolmens (Burial Chambers or large stone memorials), where you could see more than 40 dolmens (12 of them standing in a very good condition) and the rest are damaged probably by earthquakes. Also there are several menhirs, cupholes and stone alignments as well.

This area of the Levant has the highest concentration of dolmens outside of Western Europe. The Jordanian dolmen is around three meters long, one meter high and one meter wide, although some reach up to seven meters in length.

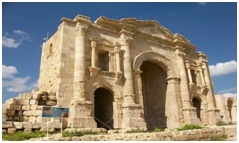

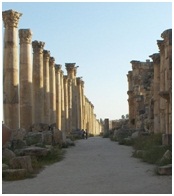

Jerash "Pompeii of the Middle East or Asia"

Jerash 48 kilometers north of the capital Amman towards Syria, known for the ruins of the Greco-Roman city of Gerasa, also referred to as Antioch on the Golden River. It is sometimes misleadingly referred to as the "Pompeii of the Middle East or Asia", referring to its size, extent of excavation and level of preservation (though Jerash was never buried by a volcano). Jerash was the home of Nicomachus of Gerasa (Greek: Νικόμαχος) (c. 60 – c. 120) who is known for his works Introduction to Arithmetic (Arithmetike eisagoge), The Manual of Harmonics and The Theology of Numbers. Recent excavations show that Jerash was already inhabited during

the Bronze Age (3200 BC - 1200 BC).

The history of Jerash goes back to prehistoric times, and on the slopes east of the Triumphal Arch can be found flint implements which show that here was the site of the Neolithic

settlement. Outside the walls to the north was a small Early Bronze Age village about 2500 B.C., and on the hilltops above are remains of dolmens of a slightly earlier period. There are now no traces of occupation during the rest of the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, but had there been settlements anywhere within the area of the Roman city they would certainly have disappeared or become buried during the course of its construction. There are many Iron Age settlements in the vicinity, and it is unlikely that a place with so fine a water supply as that of Jerash would have remained unoccupied

After the Roman conquest in 63 BC, Jerash and the land surrounding it were annexed by the Roman province of Syria, and later joined the Decapolis cities. In AD 90, Jerash was absorbed into the Roman province of Arabia, which included the city of Philadelphia (modern day Amman).

The Romans ensured security and peace in this area, which enabled its people to devote their efforts and time to economic development and encouraged civic building activity, In the second half of the first century AD, the city of Jerash achieved great prosperity.

In AD 106, the Emperor Trajan constructed roads throughout the provinces and more trade came to Jerash. The Emperor Hadrian visited Jerash in AD 129-130. The triumphal arch (or Arch of Hadrian) was built to celebrate his visit. A remarkable Latin inscription records a religious dedication set up by members of the imperial mounted bodyguard "wintering" there. The city finally reached a size of about 800,000 square meters within its walls. The Persian invasion in AD 614 caused the rapid decline of Jerash.

However, the city continued to flourish during the Umayyad Period, as shown by recent excavations. In AD 749, a major earthquake destroyed much of Jerash and its surroundings.

During the period of the Crusades, some of the monuments were converted to fortresses, including the Temple of Artemis. Small settlements continued in Jerash during the Ayyubid, Mameluk and Ottoman periods. Excavation and restoration of Jerash has been almost continuous since the 1920s.

Ancient Jerash Remains in the Greco-Roman Jerash include:

- The Corinthium column

- Hadrian's Arch

- The circus/hippodrome

- The two large temples (dedicated to Zeus and Artemis)

- The nearly unique oval Forum, which is surrounded by a fine colonnade,

- The long colonnaded street or cardo

- Two theatres (the Large South Theatre and smaller North Theatre)

- Two baths, and a scattering of small temples

- An almost complete circuit of city walls.

Most of these monuments were built by donations of the city's wealthy citizens. From AD 350, a large Christian community lived in Jerash, and between AD 400-600, more than thirteen churches were built, many with superb mosaic floors. A cathedral was built in the fourth century. An ancient synagogue with detailed mosaics, including the story of Noah, was found beneath a church.

Jerash is considered one of the most important and best preserved roman cities in the near east. It was a city of the Decapolis.

The history of Jerash goes back to prehistoric times, and on the slopes east of the Triumphal Arch can be found flint implements which show that here was the site of the Neolithic settlement.

Outside the walls to the north was a small Early Bronze Age village about 2500 B.C.

Jerash Highlights:

Hadrian’s Arch

Built to commemorate the visit of the Emperor Hadrian to Jerash in 129AD, this splendid triumphal arch was intended to become the main Southern gate to the city; however the expansion plans were never completed.

Hippodrome

This massive arena was 245m long and 52m wide and could seat 15,000 spectators at a time for chariot races and other sports. The exact date of its construction is unclear but it is estimated between the mid-seconds to third century AD.

Oval Plaza

The spacious plaza measures 90mx80m and is surrounded by a broad sidewalk and colonnade of 1st century AD Ionic columns. There are two alters in the middle, and a fountain was added in the 7th Century AD.

Colonnaded Street

Still paved with the original stones (the ruts worn by chariots are still visible) the 800m Cardo was the architectural spine and focal point of Jerash. An underground sewage system ran the full length of the Cardo and the regular holes at the sides of the street drained rainwater into the sewers.

Cathedral

Further up the Cardo Maximus, on the left is the monumental and richly carved gateway of a 2nd century Roman Temple of Dionysus. In the 4th century the temple was rebuilt as a Byzantine church now referred to as the ‘Cathedral’ (although there is no evidence that it held more importance than any of the other churches). At the top of the stairs, against an outer East wall of the Cathedral is the shrine of St. Mary, with a painted inscription to Mary and the archangels Michael and Gabriel

Nymphaeum

This ornamental fountain was constructed in 191AD and dedicated to the Nymphs. Such fountains were common in Roman cities, and provided a refreshing focal point for the city. This well-preserved example was originally embellished with marble facings on the lower level and painted plaster on the upper level, topped with a half-dome roof. Water cascaded through seven carved lion’s heads into small basins on the sidewalk and over flowed from there through drains and in to the underground sewage system.

North Theatre

The North Theatre was built in 165AD. In front is a colonnaded plaza where a staircase led up to the entrance. The theatre originally only had 14 rows of seats and was used for performances, city council meetings, etc. In 235AD, the theatre was doubled in size to its current capacity of 1,600. The theatre fell into disuse in the 5th century and many of its stones were taken for use in other buildings.

South Theatre

Built during the reign of Emperor Domitian, between 90-92AD, the South Theatre can seat more than 3000 spectators. The first level of the ornate stage, which was originally a two-storey structure, has been reconstructed and is still used today. The theatre’s remarkable acoustics allow a speaker at the centre of the orchestra floor to be heard throughout the entire auditorium without raising his voice. Two vaulted passages lead into the orchestra, and four passages at the back of the theatre give access to the upper rows of seats. Some seats could be reserved and the Greek letters which designate them can still be seen.

Jerash Archaeological Museum

Houses a fascinating collection of artifacts found at the site. These include gold jewelers, coins & glass.

Ajloun Castle is an Ayyubid castle that stands atop Jabal Auf, near Ajloun, in northern Jordan

This huge fortress was built by Izz al-Din Usama, a commander and nephew of Salah ad-Din al-Ayyubi (Saladin), in AD 1184-1185. The fortress is considered one of the very few built to protect the country against Crusader attacks from Karak in the south and Bisan in the west. From its situation, the fortress dominated a wide stretch of the northern Jordan Valley, controlled the three main passages that led to it (Wadi Kufranjah, Wadi Rajeb and Wadi al-Yabes), and protected the communication routes between south Jordan and Syria.It was built to contain the progress of the Latin Kingdom of Transjordan and as a retort to the castle of Belvoir a few miles south of the lake of Tiberias.

Another major objective of the fortress was to protect the development and control of the iron mines of Ajlun. The original castle core had four corner towers. Arrow slits were incorporated in the thick walls and it was surrounded by a fosse averaging 16 meters (about 52 feet) in width and 12–15 meters (about 39–49 feet) in depth

The castle is one of the best preserved examples of Medieval Arab-Islamic military architecture. Among its main features are a surrounding dry moat, a drawbridge into the main entrance, the fortified entrance gate, a massive south tower, and several other towers on all sides. The castle boasts a labyrinth of vaulted passages, winding staircases, long ramps, enormous rooms that served as dining halls, dormitories, and stables, and the private quarters of the Lord of the Castle (complete with a small stone bathtub and rectangular windows that convert into arrow-slits for defensive purposes).

Village of Tubna

In the nearby village of Tubna, visitors will find a Zeidani mosque and a meeting hall dating back to 1750 AD. Visitors will also find a structure known as “Al’ali Shreidah”, home of the governor of the region before the establishment of modern Jordan. The governor’s home was much admired by the contemporaries due to the fact that it was the first two-level building in the region. Settlement in Zubia Village, within the Ajlun district, dates back to the Byzantine period. There is an area in the village known as “the monastery”, which contains the remains of an old Byzantine church. There are also houses and stables dating back several hundred years. A spring located in a valley between Zubia and Tubna served as a major source of water for the surrounding settlements. Today, there are more than ten villages surrounding the Ajlun Reserve. The area is famous for its olive trees and its assorted products.

Umm al-Jimal

Deep in the heart of the "black badia", and 120 kms from Amman lie the remains of the town of Um al Jimal , The village of Umm el-Jimal originated in the first century A.D. as a rural suburb of the ancient Nabataean capital of Bostra. A number of Greek and Nabataean inscriptions found on the site date the village to this time. During this period, the population of the site is estimated at 2000-3000 people. Upon the foundation of Provincia Arabia in A.D. 106 the Romans took over the village as Emperor Trajan conquered the surrounding lands.

In the village, the Romans erected a number of buildings including the Praetorium and the large

reservoir near the castellum.After the Rebellion of

Queen Zenobia in A.D. 275, Roman countermeasures included the construction of a fort (Tetrarchic castellum) that housed a military garrison. As Roman influence in the area gradually diminished, the area once again became a rural village under control of the new Byzantine Empire. During the 5th and 6th centuries, Umm el-Jimal prospered as a farming and trading town in which the population jumped to an estimated 4000 to 6000 people. However, after the Muslim conquests of the 7th century A.D, the village population diminished even though building projects and renovations continued to take place. In AD 747/749 an earthquake destroyed much of the area and Umm el-Jimal, like other towns and villages, was abandoned. The village remained unpopulated for nearly 1100 years until the modern community developed in the twentieth century.

The village of Umm el-Jimal is located in semi-arid Northern Jordan known as the Southern Hauran, at the western edge of the desert Badiya region. The area consists mainly of the igneous rock basalt, which is the primary building material the people of the region used. Basalt also served as a natural insulation which was extremely important in the region. In the cool winter months the basalt blocks would trap the heat from the sun and would then radiate that heat throughout the structure thus acting as a natural heating source. In the hot summer months it would serve as a cooling unit because the dense nature of the blocks trapped the cool air within the structure, despite the fact that temperatures exceed 100 °F. The volcanic nature of the soil has made it one of the most fertile areas in Jordan and Syria.

Nabataean peoples were the first to build homesteads in the area in the first century A.D. The settlement was mainly a farming community and a trading outpost dependent on Bostra, the nearby capital of the Nabataeans. Though the evidence for this village survives only in fragments, there are numerous Nabataean inscriptions from this period, mostly tomb stones. At least two men mentioned on these served as members of the Bostra City Council (de Vries, Bert).

As the

Romans continued their conquest of the surrounding areas, the Nabataean King saw his state’s demise as inevitable, so he ceded his kingdom to the Roman emperor Trajan in A.D. 106. The Romans named the newly acquired territory Provincia Arabia and promptly set up local governments. The Praetorium, so named by H. C. Butler in 1905, may have been built for this purpose in the 3rd century A.D. After the rebellion led by Queen Zenobia of Palmyra in A.D. 275, everything changed. The local people were no longer allowed to govern themselves, but had to submit to harsh foreign rule. Due to its location on the fringe of the Empire, Umm el-Jimal became a military outpost complete with soldiers and a new Tetrarchic-era fort. As Roman imperial power began to diminish, this earlier castellum lost its military function, and Umm el-Jimal gradually transformed from a military station to a civilian town.

Paradoxically, from the point of view of the local Arab residents of the Hauran, this change may have been viewed as liberation rather than decline

The Roman provincial administrators were replaced by

Byzantine rulers in the fifth century. One of those, the Dux Pelagius, built smaller military quarters, the later castellum, which is now known as the Barracks. As the local population gradually converted to Christianity the town reemerged as a prosperous agricultural and trading community.

The 150 houses still standing today were constructed in this period, the 5th-6th centuries. In the 6th

century there was an explosion of church construction, 15 of which can still be seen today.

The population continued to grow, reaching an estimated 6,000 citizens.

In the 7th century, however, power of the region was ceded to the Islamic Umayyad Empire

The

Umayyad Caliphs took control of the area of Umm el-Jimal in A.D. 640 which began the Islamic Era. Much remodeling was done throughout the site so as to repurpose buildings to suit their own needs. The Praetorium and House XVIII are examples of buildings repurposed as dwelling places, while House 53 was possibly repurposed into a mosque. Despite all of this, the population decreased and the site was slowly abandoned with the help of an earthquake in A.D. 747/749 that destroyed many buildings and much of the architecture. The site was completely deserted under the Abbasid Caliphs in the ninth century.

PELLA (Tabaqat Fahl)

Is a village and the site of ancient ruins some 130 KM north of Amman. It is half an hour by car from Irbid, in the foothills of the Jordan valley, at exactly sea-level, Pella is probably the area’s richest site. With antiquities dating back to both the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, it is the place to which early persecuted Christians from Jerusalem fled. Close by this ancient settlement, the site has been continuously occupied since Neolithic times. First mentioned in the 19th century BC in Egyptian inscriptions, its name was Hellenised to Pella, perhaps to honour Alexander the Great's birthplace. The Roman city, of which some spectacular ruins remain, supplanted the Hellenistic city. During this period Pella was one of the cities making up the Decapolis.The city was the site of one of Christianity's earliest churches. According to Eusebius of Caesarea it was a refuge for Jerusalem Christians

in the 1st century AD who was fleeing the Jewish–Roman wars. Evidence has been found of some of the world’s earliest camp sites and semi-permanent villages dating back to the Natufian and Kebaran periods, 10,000 to 18,000 years ago. Together with excavated ruins from the Greco-Roman period, Pella offers visitors the opportunity to see the remains of a Chalcolithic settlement from the 4th millennium BC, evidence of Bronze and Iron Age walled cities, Byzantine churches, early Islamic residential quarters, and a small medieval mosque. The city proper was destroyed by the Golan earthquake of 749. A small village remains in the area. Only small portions of the ruins have been excavated.

Some of the world’s earliest camp sites and villages dating back 10,000 to 18,000 years

Umm Qays (Gadara)

Umm Qais, situated 110 km north of Amman on a broad promontory 378 meters above sea level with a magnificent view over the Yarmouk River, the Golan Heights, and Lake Tiberias, this town was known as Gadara, one of the most brilliant ancient Greco-Roman cities of the Decapolis; and according to the Bible, the spot where Jesus (pbuh) cast out the Devil from two demoniacs (mad men) into a herd of pigs (Mathew 8:28-34)

In ancient times, Gadara was strategically situated, laced by a number of key trading routes connecting Syria and Palestine. It was blessed with fertile soil and abundant rainwater. This town also flourished intellectually in the reign of Augustus and became distinguished for its cosmopolitan atmosphere, university's scholars, attracting writers, artists, philosophers and poets, the likes of satirist Menippos (2nd half of the 3rd century BC), the epigrammist Meleagros, and the rhetorician Theodoros (14-37 AD). Gadara was also the resort of choice for Romans vacationing in the nearby Himmet Gader Springs

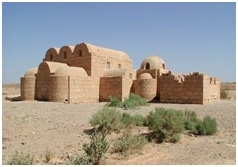

Archaeological surveys indicate that Gadara was occupied as early as the 7th century BC. The Greek historian, Polybius, described the region